Meeting: Paul D. Taylor

Following a year that saw Stonehill Taylor wrap up an iconic transformation and scoop two AHEAD awards, President and founding partner Paul Taylor talks creating hotels for the city that never sleeps.

It is Veteran’s Day in New York City, and the annual 20,000-strong parade is halfway across Chelsea by the time I reach the Stonehill Taylor offices.

On its route north from Madison Square Park – walking a mile and change up Fifth Avenue until they reach the Diamond District and 46th Street – the procession will rarely find itself more than a few blocks from a hotel the firm had a hand in. The NoMad on 28th will see them off, with Moxy Chelsea located just a few minutes walk east. Ace Hotel unfolds on the left a couple of blocks later, so too St. Regis as they close in on St. Patrick’s Cathedral. Then The Whitby, more or less overlooking the finish line to play them out.

Up in the office, we meet in a room showcasing a selection of trophies and awards the 87-person firm has received. Amongst the highlights are a brace of AHEAD Americas awards from 2019; one for the eponymous restaurant at NoMad Las Vegas – where the studio translated its acclaimed concept for the original NYC project to the sin city strip – alongside two finalist places for their interior design scheme at the Eliza Jane Hotel – a heritage project built within seven internally conjoined historic warehouses in New Orleans – and their work as architect at the Moxy Chelsea, a 37-storey industrial greenhouse inspired newbuild, atop which the ambitiously realised Fleur Room sits. A year previous, the firm had taken home the Suite award for its architectural work at The Whitby.

Later in the conversation, Paul D. Taylor, President of Stonehill Taylor, will tell me that he faced a challenge when starting out, in that he had won no prizes at the time, and thus lacked the valuable networking and social currency they provide. When I point to the veritable haul behind us, he laughs, and explains “don’t worry, I saved those for later”.

The Stonehill Taylor portfolio stretches from Portland to Fort Lauderdale, and across the hospitality, residential, education and health sectors, though above all, it has become a specialist in New York hotels.

Born and raised a couple of stops South in Greenwich Village, then educated over the river at the Pratt Institute, Taylor would have walked past the buildings that his company’s work would come to define often. If ever the term stomping ground was applicable in such a global industry, the veteran architect could lay solid claim to The Big Apple being his.

At school, Taylor excelled in maths and science, whilst his artist parents oversaw more creative endeavours at home. Applying for his new school’s art programme in fifth grade, Taylor’s mother was called in to explain why the ten-year-old had submitted an adult’s work as his own. For a while he saw himself a scientist, but success in a later competition had him reconsider. “Add math, science and art together and you get architecture,” a friend had remarked. Completing a five-year college programme in four, Taylor was a practicing interior architect at 22, and hired by what was then Lundquist & Stonehill by 24.

In an era when interior design was something of an afterthought, Taylor was tapped for his keen aesthetic eye, bringing a valuable presence to the table that would see him holding a 50% stake in the firm upon Oliver Lundquist’s retirement in 1986. Early success came in the form of a project for investor Harry B. Macklowe, as production architect for the interiors of what is now the Millennium Hotel off Times Square. Disrupted by the savings and loan crisis, however, the project saw its investor go bankrupt, and Singapore’s CDL, who already had a controlling interest in the Millenium Hotel chain worldwide, snap up the site along with a controlling interest in the Plaza Hotel. As the seemingly doomed hotel’s listed architect, Taylor was called in by Chase Manhattan to work on the property before it was handed over, then subsequently became the chain’s Master Architect when the transaction was complete.

A decade and 10 major projects later, Taylor returned to New York having cut his teeth across the country, with one of his final undertakings in this role the restoration of the Millennium hotel in Lower Manhattan following 9/11. With Stonehill set to retire, and Taylor having uncovered an exceptional niche, he found himself back home, ready to step back into the firm and begin the impressive run of work that brings us to today. The studio became Stonehill & Taylor, before the ampersand was dropped as part of a sleek 2017 rebrand. “It was perfect because we could do the whole thing,” he explains. “Covering both architecture and interiors allowed us to really think about the bigger picture and consider the experience.”

Balanced between its interiors and architecture departments – which work together and independently across the studio’s slate of projects – Stonehill Taylor has forged close collaborations with hoteliers and developers who value the breadth of the firm’s operational scope. Beyond architecture and design, Taylor explains that he and his company have long looked beyond the traditional responsibilities of what he refers to as the “capital A” architect.

“I have always taken a bigger role than asked,” he says. “At first it was how we made business, but now it’s the reason people come to us. I’ve always been flexible working in a given situation and would never want to say this is what architects do, no more, no less – if it’s a great project we’ll go above and beyond.”

At the Millennium Hilton restoration this meant overseeing board reports, insurance claims, consultancy recruitment and more on top of his role as a designer; an on-the-job education in everything else that goes into a hotel besides design. This fluency later saw him connect with Tim and Kit Kemp of Firmdale Hotels – advising the duo on suitable Manhattan locations for the group’s US debut, The Crosby Street Hotel – then facilitate their vision of fusing New York’s metropolitan spirit with Firmdale’s decidedly British flavour. Eight years later, when the Kemps returned to explore the possibility of a follow up, Taylor’s firm was an obvious choice for partner, and the special relationship bore its second fruit in The Whitby.

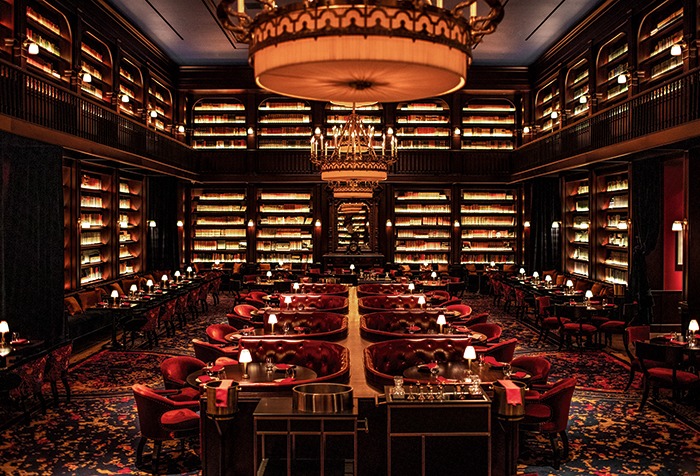

Likewise, with Sydell Group Taylor oversaw the first NoMad hotel – working with designer Jacques Garcia to emulate Paris’ Costes Hotel – then its Las Vegas counterpart that channels elements of the original. An ongoing agreement with Manhattan-based developer Lightstone has seen Stonehill Taylor design the architecture for five Moxy hotels in New York alone, subsequent to having played a large role in defining the brand’s playful character. “As a designer you’re helping to identify the business and model as much as you are colours that match and the right set of curtains.” he says.

Two more Moxys are currently in the works in Bowery and Brooklyn, but whilst differentiating five identically branded hotels within the same quilt of urban fabric may sound like a daunting task, each of the series has gone on to develop its own coherent identity. The corten steel exterior grid and the greenhouse-esque façade cladding Moxy Chelsea, for instance, remain a far cry visually from the neon dazzle of Moxy Times Square, and even further from the bohemian Moxy East Village. Each bears the Moxy name and level of service, though each demonstrates a level of detail drawn from the locale that only a New York native would be familiar with. This partnership in particular has afforded Taylor a vantage point from which to observe the habits and values emerging across the incoming class of younger guests.

“Each generation is a little bit different from the last, but also a little bit the same,” he notes. “There are two factors that will determine the direction of the hospitality industry. The first is the high cost of real estate in urban contexts, and the shrinking of room sizes this results in – because if you cannot justify a project financially in this market then it will not be made. The second is the hotel as a destination, which it now must be in itself, and not simply somewhere to explore a location from. There must absolutely be a sense that, in choosing a hotel, the guest is creating a key part of their overall experience. When these ideas reach across to other price points there will be a drastic redefinition of what luxury really means.”

However, Taylor has perhaps already played a part in this redefinition with the 2019 launch of TWA Hotel occupying Eero Saarinen’s iconic former JFK terminal, where the firm designed guestrooms and public spaces and worked with a team of four other studios to transform the landmark structure’s function whilst simultaneously retaining, channelling and continuing the spirit of its form. “That was a big one,” Taylor smiles. “What we did there actually plays into one of my favourite concepts from throughout my career – returning something back to what it never was. TWA was never a hotel, so how did we achieve this? Well, the word authenticity is very tricky, and thrown around loosely these days, yet in those guestrooms there are three authentic things Saarinen did – the womb chair, the tulip table and executive chair, which are still as contemporary as any designer working today. He never knew it would be a hotel, but those spaces feel coherent, like they are part of the history and journey through terminal.”

Indeed, a close reading of Saarinen’s vision in tandem with a deep-dive of TWA and jet age aesthetics resulted in one of the year’s most talked about openings, with the firm’s work ensuring what was never a hotel feels like it always has been. Within guestrooms, the studio’s own product designs sit alongside Saarinen’s to create schemes that recommence the building’s story as opposed to simply channelling it. Saarinen himself once worked and roomed with Taylor’s former boss, Lundquist, designing information packets for the OSS, a wartime intelligence agency and predecessor to the CIA. It may have taken a while, but the brief connection came full circle. “I was very proud of how our work feels sympathetic with the whole experience, whilst still allowing Saarinen to be the hero,” he notes.

Though the project may differ vastly from comparable price points, TWA perhaps signals a sea change, with guests ready to pay premium rates to experience a unique kind of statement design. It may be a few more stops on the subway than Taylor is used to, though doubtless opens a new chapter in both the contexts of New York’s hospitality scene and the firm itself’s more recent history. Whilst Taylor admits that expanding the studio’s slate of international projects could benefit their sustainability long term, business remains strong in New York, with the city recording the highest national levels in occupancy, ADR and RevPAR benchmarks through 2018, making it the best performer in the country – one that shows no signs of slowing down. Designing a resort in the Bahamas would certainly be nice, he acknowledges, however it is perhaps the many years that Taylor has spent traversing the streets directly below us that now sees him a paradoxical expert in creating hotels for a city they say never sleeps.

By the time I leave the office, the Veteran’s Day parade has almost finished its march, the route following a spine of prominent hotels that trace both the manner in which the Big Apple’s hospitality landscaped has changed, and the hand in which our man in New York and his studio have had in changing it.

Words: Kristofer Thomas

Portrait image: © Gerardo Vizmanos

This article originally ran in Sleeper 88.

Related Posts

4 October 2018

MEETING: Priya Paul

30 November 2015

European Hotel Design Awards 2015

21 January 2015